How do utility companies monitor thousands of miles of electrical wire to find small imperfections that threaten the entire system? For the entire history of electrical infrastructure, the only answer has been ‘very slowly.’

Now, Sparrow’s computer vision capabilities, combined with Fast Forward’s thermal imaging system, can accomplish what used to take over a decade in less than a month. Here’s how they do it.

How it Started

Dusty Birge, CEO of Fast Forward began inspecting power lines using a drone and crowd-sourced labor. He knew that automation would be needed to take the next step forward, but he found people in the artificial intelligence space to be overconfident and unreliable. That is until he was introduced to Ben Cook, the founder of Sparrow Computing.

Within a month, Ben provided a computer vision model that could accurately identify utility poles, and that has been continually improving ever since.

The Project

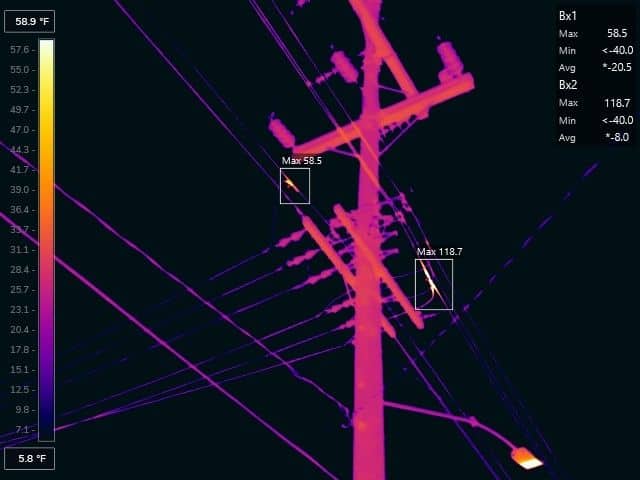

Fast Forward rigged a system of 5 thermal cameras to a car and set them to take photos every 15 feet. Sparrow’s computer vision model then ran through the nearly 2 million photos taken and extracted about 50,000 relevant images, detecting any abnormalities in the utility lines.

“Right out of the gate, we presented data to the utilities and just blew them away,” Dusty said in an interview. “The first test runs proved a scalable model that automatically monitored a company’s entire system in under a month, where traditional methods would take over a decade. These test runs successfully spotted anomalies that would have caused blackouts, but were instead able to be fixed promptly.”

The numbers speak plainly for themselves, not just in time but in cost as well. There was one hotspot that Sparrow identified, but that the utility company did not address in time. The power line failed as a result, costing the company around $800. The inspection itself cost only $4. The potential return of this technology is astronomical, and it is already being put to good use.

Going Forward

Fast Forward is already looking ahead to the next phase of this project, translating the same process to daytime cameras. Having had such success in the initial tests, Dusty is pleased to continue working with Ben and Sparrow Computing.

Ben is excited to find more real world problems that can be solved as cameras become cheaper and more ubiquitous. He wants to create more computer vision models that interact with the physical environment and revolutionize companies throughout the Midwest and the world.

To get a closer look at Sparrow Computing, reach Ben at ben@sparrow.dev.